1. INTRODUCTION

- Propionibacterium acnes (P. acnes): one of the factors causing acne.

- Antibiotic therapy in acne

- The failure relates to resistant propionibacterium strains.

- Antibiotic resistant characteristics vary in different countries.

- Antibiotic resistant in USA in 1979 and then in Europe, Asia, South America à the emergence of antibiotic resistance

- In HDV, the rate of prescriptions including antibiotics was 75.8% in 2011.

- References derived from foreign documents.

- This study aims to

- determine the prevalence and pattern of antibiotic-resistant Propionibacterium acnes and

- identify association between factors: disease duration, family history of acne with the resistant strains in patients

2. METHODS

- Patients

This was a case series study.

Eighty-seven patients were included in the study.

Clinical information, including age, gender, disease duration, family history of acne were obtained.

- Methods

Culture and identification of P. acnes

Patients’ samples were extracted by two trained technicians in Laboratory Department of HDV.

Laboratory of Bacteria, Pasteur Institute of HCMC.

Determination of Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC).

Resistant breakpoints for antimicrobials were defined according to the European Committee on antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST):

clindamycin ≥ 0.25 µg/ml,

tetracycline ≥ 2 µg/ml,

minocycline ≥ 1 µg/ml, doxycycline ≥ 1 µg/ml,

trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole ≥ 1 µg/ml.6

azithromycin ≥ 4 µg/ml (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute – CLSI)

levofloxacin, ≥ 0.25 µg/ml (CLSI)

- MIC differences regarding duration, family history of acne

- The MIC of 7 different antibiotics were compared:

(i) Between disease duration of less than 24 months and more than 24 months;

(ii) between patients with and without family history of acne

3. RESULTS AND DICUSSION

87 acne patients: 59 females and 28 males.

The patients’ age ranged from 14 to 34 years with a mean of 22 years.

87 specimens, P. acnes strains were isolated from 42 (48.3%).

Of these 42 patients:

- 26 patients with a family history of acne,

- 6 without family history;

- 34 had disease duration for more than 24 months

- 8 less than 24 months

| P. acnes | n | (%) |

| (+) | 42 | 48,3 |

| (-) | 45 | 51,7 |

| TOTAL | 87 | 100 |

Prevalence of P.acnes isolated: 48,3%

Table 1. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) of the antibiotics for 42 Propionibacterium acnes isolated

| Antibiotics | Number of isolates inhibited at various MIC (µg/ml) | MIC 50 | MIC 90 | Resistance

breakpoint |

||||||||||||||

| 0.015 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 256 | ||||

| AZM | 4 | 21 | 7 | 1 | 2 | – | 6 | – | 1 | ≥0.25 | ≥16 | ≥4* | ||||||

| CLI | 5 | 15 | 9 | 1 | 12 | ≥0.5 | ≥4 | 0.25** | ||||||||||

| TET | 1 | – | 20 | 18 | 3 | – | – | – | ≥0.25 | ≥1 | 2** | |||||||

| DOX | 1 | 16 | 4 | 18 | 3 | – | – | – | ≥0.25 | ≥0.5 | 1** | |||||||

| MNO | 2 | 37 | 2 | 1 | – | – | – | ≥0.06 | ≥0.125 | 1** | ||||||||

| LVX | 4 | 14 | 24 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ≥0.5 | ≥1 | ≥8* | ||||||

| SXT | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 1 | – | – | 19 | 8 | ≥16 | ≥256 | ≥1** | |||||

**Resistant breakpoints of EUCAST *Resistant breakpoints of CLSI

AZM: Azithromycin; CLI: clindamycin; TET: tetracycline; DOX: doxycycline; MNO: minocycline; LVX levofloxacin; SXT: sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim

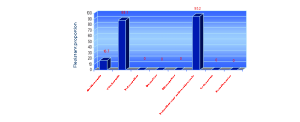

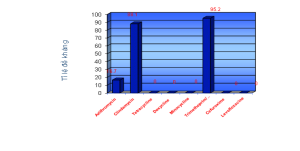

Figure 1 General prevalence of antimicrobial resistance.

y-axis shows percentage of resistant strains

Prevalence of antimicrobial resistance

Resistant to

- Azithromycin: 7 strains (16.7%)

Clindamycin: 37 strains (88.1%)

Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole: 40 (95.2%).

- None of them was resistant to tetracycline, doxycline, minocycline, levofloxacin.

- Twenty-eight (67%) strains were resistant to 2 antibiotics (SXT + CLI)

- seven (16.7%) strains were resistant to 3 antibiotics (AZI + CLI + SXT)

- All strains resistant to AZI were also resistant to CLI

4. DISCUSSION

The antibiotics resistance in P. acnes is increasing over the world in American, Europe, Asia.

P. acnes resistant to the macrolides are the most common.

Combined resistance to clindamycin and erythromycin was common*

In France, 75.1% patients resistant to erythromycin and only 9.5% to tetracycline**.

*Coates P, Vyakrnam S, Eady EA, Jones CE, Cove JH, Cunliffe WJ. Prevalence of antibiotic-resistant propioni-bacteria on the skin of acne patients: 10-year surveil-lance data and snapshot distribution study. Br J Dermatol 2002; 146: 840–848

** Ross JI, Snelling AM, Carnegie E et al. Antibiotic-resistant acne: lessons from Europe. Br J Dermatol 2003; 148: 467–478

In Asia, the prevalence of P. acnes resistant to the macrolides was the most common too.

In Singapore, resistant rate more than 50% and tetracycline⁄doxycycline resistant rate only 11.5%*

In 2011, Luk et al emphasized that the resistance to clindamycine and erythromycin were the highest in Hongkong **

* Tan H.H, W.H. Tan A.W.H, et al. (2007), “Community-based study of acne vulgaris in adolescents in Singapore”, British Journal of Dermatology, 157, pp.547-551

** Luk N.-M.T., M. Hui, et al. (2011), “Antibiotic-resistant Propionibacterium acnes among acne patients in a regional skin centre in Hong Kong”, Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology

| NC | ERT | AZT | CLI | TET | DOX | MIN | LEV | SXT | CEF |

| (%) | |||||||||

| H-H. Tan

Singapore |

69.2 | 50 | 11.5 | 23 | 11.5 | 38.5 | |||

| M. Song

Korea |

0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| N.-M.T. Luk

Hongkong |

20.9 | 53.5 | 16.3 | 16.3 | 16.3 | ||||

| N. Ishida Japan | 10.4 | 8.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| This study | 16.7 | 88.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 95.2 | 0 | |

The pattern of antibiotic-resistant P. acnes in this study seems to be similar with those in the Asia.

P.acnes resistant to the MLS (clindamycine and azithromycine) are higher than the tetracyclines (88.1%, 16.7% compare with 0%)

In Vietnam, there are many possible ways interfering with the antibiotic resistance of P. acnes.

The combination between topical and oral antibiotics, has been increasing P. acnes strains resistant to antibiotics*.

In Vietnam: A lot of topical products containing clindamycine, alone or combination; those can be bought easily in the pharmacies without doctors’ prescriptions.

In a community-based study in 2007, 78 percent antibiotics were purchased in private pharmacies **.

Buying directly drugs is cheaper and faster than going to a practioner

-> Uncontrolled using antibiotics: first reason

* Eady AE, Cove JH, et al. (2003), “Is antibiotic resistance in cutaneous propionibacteria clinically relevant? Implications of resistance for acne patients and prescribers”, Am J Clin Dermatol, 4, pp.813–831

** Nguyễn Văn Kính và Nhóm Nghiên cứu Quốc gia của GARP-Việt Nam (2010), Phân tích thực trạng: Sử dụng kháng sinh và kháng kháng sinh ở Việt Nam, Hà Nội CDDEP, Global Antibiotics Resistance Partnership, pp: v-vi

Antibiotics Macrolides have been widely prescribing to treat other infectious diseases.

In a survey in a general hospital, Nguyen Thi Thu Ba reported that the most common antibotic groups were *

- Beta-lactamine (60,29%),

- Aminoglycoside (13,15%),

- Quinolone (10,64%),

- Nitro-imidazole (8,18%)

- Macrolide (3,43%).

contacting with antibiotics many times -> resitance : second reason

* Nguyễn Thị Thu Ba (2007), “Tình Hình Sử Dụng Kháng Sinh Tại Bệnh Viện Hoàn Mỹ Đà Nẵng Từ Tháng 01/2007 đến tháng 10/2007 “, Nội San Y Khoa, pp.26-28

Ross et al mentioned the contagion from the patients who get resistant strains*

-> Third reason

* Ross JI, Snelling AM, Carnegie E et al. Antibiotic-resistant acne: lessons from Europe. Br J Dermatol 2003; 148: 467–478

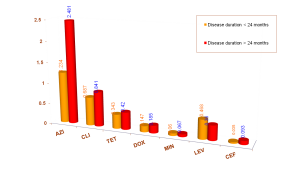

Table 2a. Mean MIC of antibiotics relating to disease duration

| Disease duration | AZI

µg/ml |

CLI

µg/ml |

ROX

µg/ml |

TET

µg/ml |

DOX

µg/ml |

MIN

µg/ml |

LEV

µg/ml |

SXT

µg/ml |

CEF

µg/ml |

| < 24 months | 1.234

± 2.735 |

0.687 ± .578 | 2.085

± 5.622 |

0.343 ±0.129 | 0.147 ±0.089 | 0.060 ±0.000 | 0.468 ±0.088 | 83.125

±92.373 |

0.035 ±0.021 |

| ≥ 24 months | 2.481

± 5.893 |

0.841 ±0.820 | 3.706

± 8.560 |

0.420 ±0.224 | 0.185 ±0.134 | 0.067 ±0.036 | 0.360 ±0.146 | 114.176 ± 91.768 | 0.093 ±0.103 |

| P | 0.449 | 0.719 | 0.630 | 0.177 | 0.123 | 0.569 | 0.154 | 0.818 | 0.171 |

No statistically significant difference between disease duration groups

Table 2a. Mean MIC of antibiotics relating to disease duration

The MIC tended to be higher in the patient group ≥ 24 months than those < 24 months

The longer the disease last à the patients seek treatment à contacting antibiotics à getting resistant strains

Mean MIC of two groups patients with acne for more than 24 months and less than 24 months were surveyed but no significant difference found out.

However, MIC values of the first group trended higher than the second one (Table 2a).

Another study done in Korea had the same comment *

* Song Margaret, Sang-Hee SEO Hyun-Chang KO, et al. (2011), “Antibiotic susceptibility of Propionibacterium acnes isolated from acne vulgaris in Korea”, Journal of Dermatology, 38, pp.667–673

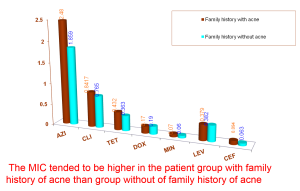

Table 2b. Mean MIC of antibiotics relating to family history of acne (FHA)

Ross showed that antibiotic resistant P.acnes may spread from patients to close contacts*

Mean MIC of two groups patients with/without family history of acne were surveyed but no significant difference found out.

Once again, MIC values of the group with family history of acne trended higher than the group without

MIC90 : inhibit the growth of 90% of organisms.

Surveying MIC90 can supply an objective data on antibiotic resistance at the fixed period.

Prevalence of P. acnes strains resistant to the tetracyclines in this study are 0%, like the result of Song’s study done in Korea, but their MIC90 are higher than those in Korea many times.

Song’s comment: The MIC90 of tetracycline, erythromycin and clindamycin have increased or remained constant over a decade *

* Song Margaret, Sang-Hee SEO Hyun-Chang KO, et al. (2011), “Antibiotic susceptibility of Propionibacterium acnes isolated from acne vulgaris in Korea”, Journal of Dermatology, 38, pp.667–673

| ERT | AZT | CLI | TET | DOX | MIN | LEV | SXT | CEF | |

| (µg/ml) | |||||||||

| M. Song

Korea |

0,047 | 0,125 | 0,250 | 0,250 | 0,125 | ||||

| N.-M.T. Luk, Hongkong | ≥128 | ≥128 | 4 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| N. Ishida

Japan |

2 | 1 | 4 | 0,5 | 2 | ||||

| This study | ≥16 | ≥4 | ≥1 | ≥0,5 | ≥0,125 | ≥1 | ≥256 | ≥0,25 | |

Table 3: MIC90 of Propionibacterium acnes to various antibiotics in some studies in Asia

In Japan, topical and oral antibiotics are prescribed commonly in acne. So, is this a reason that contributes to the MIC90 of the antibiotics tetracyclines and levofloxacin higher than those in Korea and Viet Nam

In the future MIC of some P. acnes strains in Vietnam will be able to reach the resistant breakpoint of the tetracyclines.

A high MIC is a warning sign for prescription.

After detecting MICs increased from 0.1% to 1.5% for cefixime àCDC no longer recommends cefixime as an effective oral treatment for gonorrhea *.

* Update to CDC’s Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2010: Oral Cephalosporins No Longer a Recommended Treatment for Gonococcal Infections, August 10, 2012 / 61(31); 590-594

In conclusion, our study showed that P. acnes are highly resistant to clindamycin, and SXT.

Therefore, in antibiotic therapy of acne vulgaris, it is not advisable to use Clindamycin and Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole as a first choice in HDV HCMC.